This article was first published on Medium.

This tutorial will tell you how to get started with Cucumber-jvm in Java. It is intended as a brief, easy guide. For more examples on how to use Cucumber with Java or Kotlin, check the links at the bottom of this tutorial.

Prerequisites

To get started with Cucumber in Java, you will need the following:

Setting up the project

First, we need to set up the project so we can use Cucumber.

Create a Maven project

In this tutorial, we’re using Maven to import external dependencies. We start by creating a new Maven project, which will automatically create some of the directories and files we will need.

To create a new Maven project in IntelliJ IDEA:

- Click the menu option File > New > Project

- In the New project dialog box, select Maven on the left (if it isn’t already selected)

- Make sure that the Project SDK is selected (for instance, Java 1.8) and click Next

- Specify a GroupId and ArtifactId for your project and click Next

- Specify a Project name and Project location for your project (if needed) and click Finish

You should now have a project with the following structure:

├── pom.xml

└── src

├── main

│ └── java (marked as sources root)

│ └── resources (marked as resources root)

└── test

└── java (marked as test sources root)

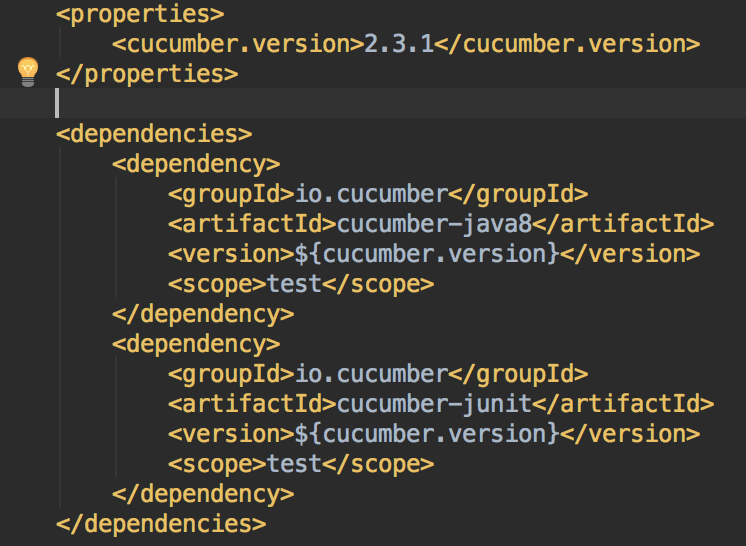

Add Cucumber to your project

Add Cucumber to your project by adding a dependency to your pom.xml:

<dependencies>

<dependency>

<groupId>io.cucumber</groupId>

<artifactId>cucumber-java</artifactId>

<version>2.3.1</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

</dependencies>

In addition, we need the following dependencies to run Cucumber with JUnit:

<dependencies>

...

<dependency>

<groupId>io.cucumber</groupId>

<artifactId>cucumber-junit</artifactId>

<version>2.3.1</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency> <dependency>

<groupId>junit</groupId>

<artifactId>junit</artifactId>

<version>4.12</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

</dependencies>

If you have IntelliJ IDEA configured to auto-import dependencies, it will automatically import them for you. Otherwise, you can manually import them by opening the Maven Projects menu on the right and clicking the Reimport all Maven Projects icon on the top left of that menu. To check if your dependencies have been downloaded, you can open the External Libraries in the left Project menu in IntelliJ IDEA.

To make sure everything works together correctly, open a terminal and navigate to your project directory (the one containing the pom.xml file) and enter mvn clean test.

You should see something like the following:

[INFO] Scanning for projects...

[INFO]

[INFO] -------------------------------------------------------------

[INFO] Building cucumber-tutorial 1.0-SNAPSHOT

[INFO] ------------------------------------------------------------- <progress messages....>[INFO] -------------------------------------------------------------

[INFO] BUILD SUCCESS

[INFO] -------------------------------------------------------------

[INFO] Total time: <time> s

[INFO] Finished at: <date> <time>

[INFO] Final Memory: <X>M/<Y>M

[INFO] -------------------------------------------------------------

Your project builds correctly, but nothing is tested yet as you have not specified any behaviour to test against.

Specifying Expected Behaviour

We specify the expected behaviour by defining features and scenarios.

The feature describes (part of) a feature of your application, and the scenarios describe different ways users can use this feature.

Creating the Feature Directory

Features are defined in .feature files, which are stored in the src/test/resources/ directory (or a sub-directory).

We need to create this directory, as it was not created for us. In IntelliJ IDEA:

- In the Test folder, create a new directory called

resources. - Right click the folder and select Mark directory as > Test Resources Root.

- You can add sub-directories as needed. Create a sub-directory with the name of your project in

src/test/resources/

Our project structure is now as follows:

├── pom.xml (containing Cucumber and JUnit dependencies)

└── src

├── main

│ └── java (marked as sources root)

│ └── resources (marked as resources root)

└── test

├── java (marked as test sources root)

└── resources (marked as test resources root)

└── <project>

Creating a Feature

To create a feature file:

- Open the project in your IDE (if needed) and right-click on the

src/test/resources/<project> folder. - Select New > File

- Enter a name for your feature file, and use the

.feature extension. For instance, belly.feature.

Our project structure is now as follows:

├── pom.xml (containing Cucumber and JUnit dependencies)

└── src

├── main

│ └── java (marked as sources root)

│ └── resources (marked as resources root)

└── test

├── java (marked as test sources root)

└── resources (marked as test resources root)

└── <project>

└── belly.feature

Files in this folder with an extension of .feature are automatically recognized as feature files. Each feature file describes a single feature, or part of a feature.

Open the file and add the feature description, starting with the Feature keyword and an optional description:

Feature: Belly

Optional description of the feature

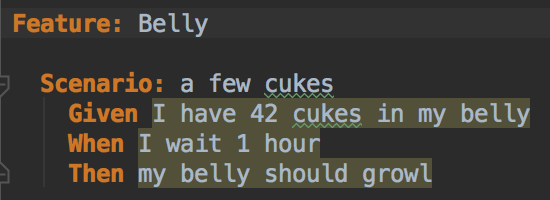

Creating a Scenario

Scenarios are added to the feature file, to define examples of the expected behaviour. These scenarios can be used to test the feature. Start a scenario with the Scenario keyword and add a brief description of the scenario. To define the scenario, you have to define all of its steps.

Defining Steps

These all have a keyword (Given, When, and Then) followed by a step. The step is then matched to a step definition, which map the plain text step to programming code.

The plain text steps are defined in the Gherkin language. Gherkin allows developers and business stakeholders to describe and share the expected behaviour of the application. It should not describe the implementation.

The feature file contains the Gherkin source.

- The

Given keyword precedes text defining the context; the known state of the system (or precondition). - The

When keyword precedes text defining an action. - The

Then keyword precedes text defining the result of the action on the context (or expected result).

The scenario will look this:

Scenario: a few cukes

Given I have 42 cukes in my belly

When I wait 1 hour

Then my belly should growl

Running the test

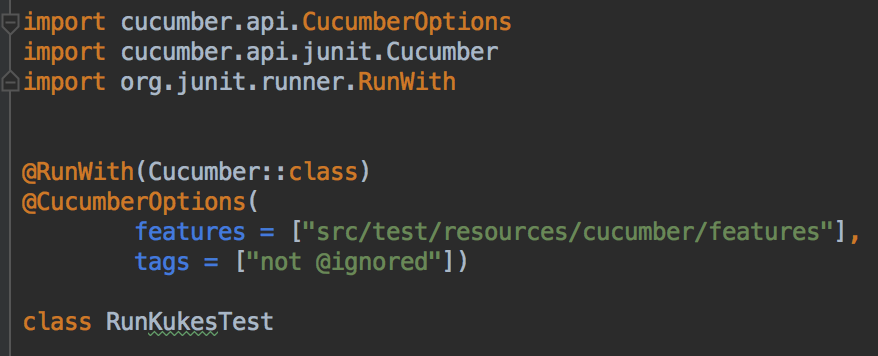

To run the tests from JUnit we need to add a runner to our project.

Create a new Java class in your src/test/java/<project> directory, called RunCucumberTest.java:

package <project>;

import cucumber.api.CucumberOptions;

import cucumber.api.junit.Cucumber;

import org.junit.runner.RunWith;

@RunWith(Cucumber.class)

@CucumberOptions(plugin = {"pretty"})

public class RunCucumberTest{

}

Our project structure is now as follows:

├── pom.xml (containing Cucumber and JUnit dependencies)

└── src

├── main

│ └── java (marked as sources root)

│ └── resources (marked as resources root)

└── test

├── java (marked as test sources root)

│ └── <project>

│ └── RunCucumberTest.java

└── resources (marked as test resources root)

└── <project>

└── belly.feature

The JUnit runner will by default use classpath:package.of.my.runner to look for features. You can also specify the location of the feature file(s) and glue file(s) you want Cucumber to use in the @CucumberOptions.

You can now run your test by running this class. You can do so by right-clicking the class file and selecting RunCucumberTest from the context menu.

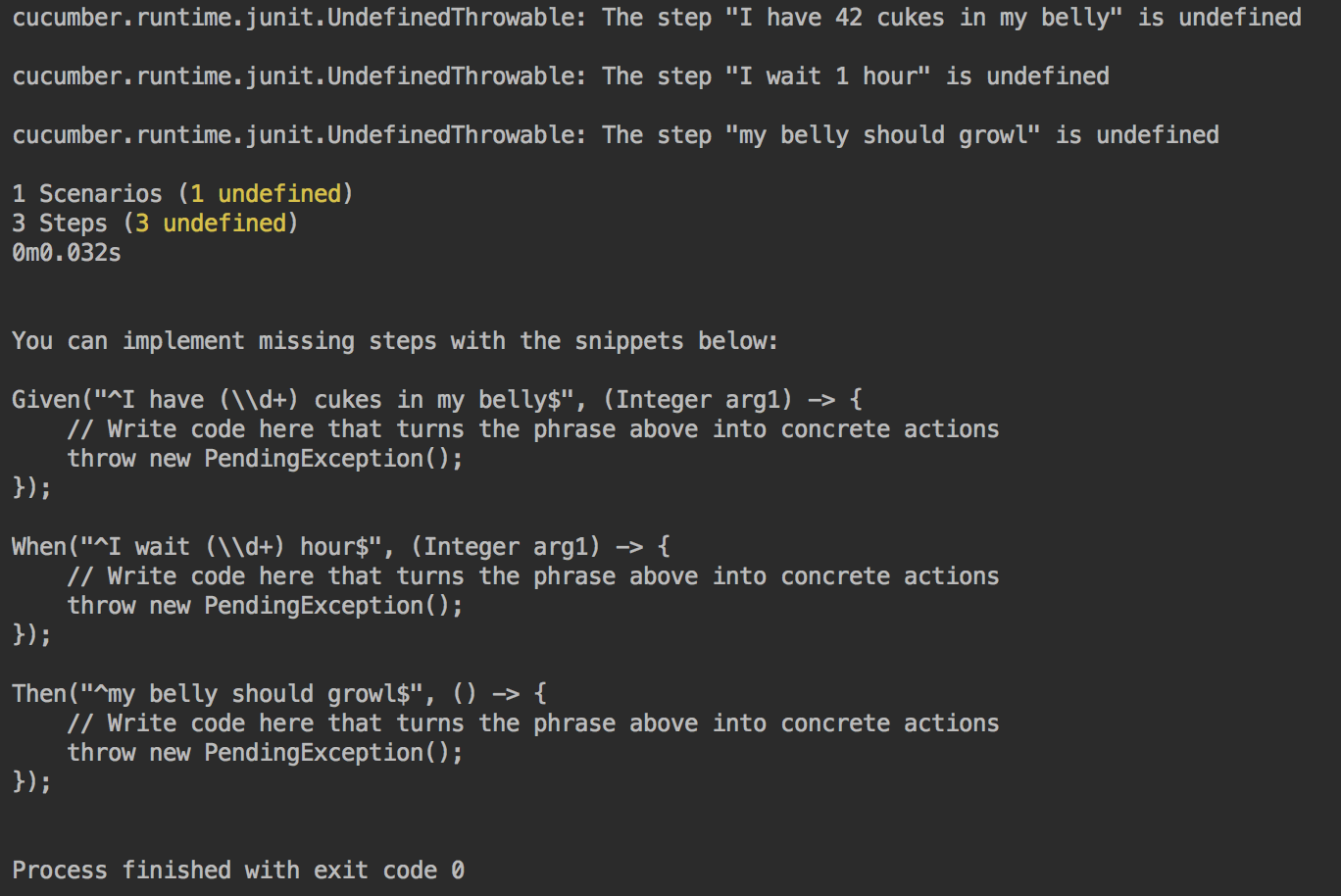

You should get something like the following result:

1 Scenarios (1 undefined)

3 Steps (3 undefined)

0m0.015s

You can implement missing steps with the snippets below:@Given("^I have (\\d+) cukes in my belly$")

public void i_have_cukes_in_my_belly(int arg1) throws Exception {

// Write code here that turns the phrase above into concrete actions

throw new PendingException();

}@When("^I wait (\\d+) hour$")

public void i_wait_hour(int arg1) throws Exception {

// Write code here that turns the phrase above into concrete actions

throw new PendingException();

}@Then("^my belly should growl$")

public void my_belly_should_growl() throws Exception {

// Write code here that turns the phrase above into concrete actions

throw new PendingException();

}

Process finished with exit code 0

As we can see, our tests have run, but have not actually done anything — because they are not yet defined.

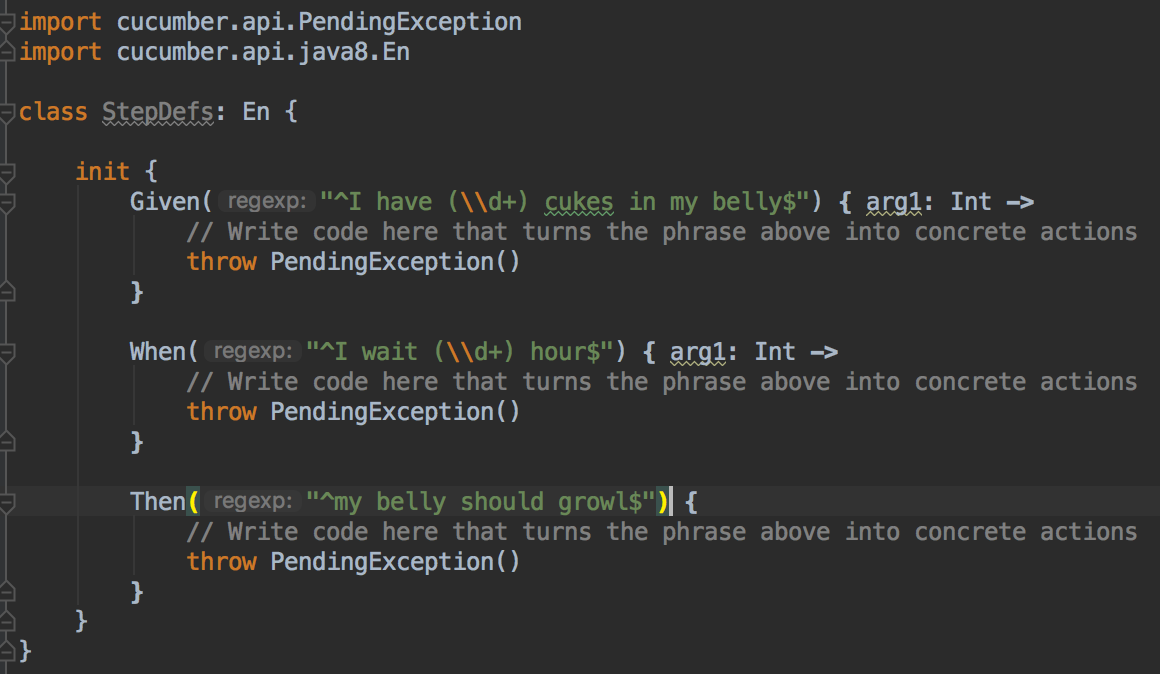

Define Snippets for Missing Steps

We now have one undefined scenario and three undefined steps. Luckily, Cucumber has given us examples, or snippets, that we can use to define the steps.

To add them to a Java class in IntelliJ IDEA:

- Create a new Java class in your

src/test/java/<project> folder (for instance, StepDefinitions.java) - Paste the generated snippets into this class

IntelliJ IDEA will not automatically recognize those symbols (like @Given, @When, @Then), so we’ll need to add import statements. In IntelliJ IDEA:

- Add import statements for

@Given, @When, @Then (underlined in red)

In IntelliJ IDEA you can do so by putting your cursor on the @Given symbol and press ALT + ENTER, then select Import class.

Our project structure is now as follows:

├── pom.xml (containing Cucumber and JUnit dependencies)

└── src

├── main

│ └── java (marked as sources root)

│ └── resources (marked as resources root)

└── test

├── java (marked as test sources root)

│ └── <project>

│ └── RunCucumberTest.java

│ └── StepDefinitions.java

└── resources (marked as test resources root)

└── <project>

└── belly.feature

Now, when you run the test, these step definitions should be found and used.

Note: Run configurations

If this does not work, select Run > Edit Configurations, select Cucumber java from the Defaults drop-down, and add the project name to the Glue field on the Configuration tab.

Your result will include something like the following:

cucumber.api.PendingException: TODO: implement me

at skeleton.Stepdefs.i_have_cukes_in_my_belly(Stepdefs.java:10)

at ✽.I have 42 cukes in my belly(/Users/maritvandijk/IdeaProjects/cucumber-java-skeleton/src/test/resources/skeleton/belly.feature:4)

The reason for this is that we haven’t actually implemented this step; it throws a PendingException telling you to implement the step.

Implement the steps

We will need to implement all steps to actually do something.

- Update your

StepDefinitions.java class to implement the step definition.

The step can be implemented like this:

@Given("^I have (\\d+) cukes in my belly$")

public void I_have_cukes_in_my_belly(int cukes) throws Throwable {

Belly belly = new Belly();

belly.eat(cukes);

}

To make this step compile we also need to implement a class Belly with a method eat().

- Implement the class

Belly.java inside your src/main/java/<project> folder; create your <project> directory here (if needed)

Our project structure is now as follows:

├── pom.xml (containing Cucumber and JUnit dependencies)

└── src

├── main

│ └── java (marked as sources root)

│ │ └── <project>

│ └── Belly.java

│ └── resources (marked as resources root)

└── test

├── java (marked as test sources root)

│ └── <project>

│ └── RunCucumberTest.java

│ └── StepDefinitions.java

└── resources (marked as test resources root)

└── <project>

└── belly.feature

Now you run the test and implement the code to make the step pass. Once it does, move on to the next step and repeat!

PendingException

Once you have implemented this step, you can remove the statement throw new PendingException(); from the method body. The step should no longer thrown a PendingException, as it is no longer pending.

Result

Once you have implemented all your step definitions (and the expected behaviour in your application!) and the test passes, the summary of your results should look something like this:

Tests run: 5, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0, Time elapsed: 0.656 secResults :Tests run: 5, Failures: 0, Errors: 0, Skipped: 0[INFO] -------------------------------------------------------------

[INFO] BUILD SUCCESS

[INFO] -------------------------------------------------------------

[INFO] Total time: 5.688 s

[INFO] Finished at: 2017-05-22T15:43:29+01:00

[INFO] Final Memory: 15M/142M

[INFO] -------------------------------------------------------------

Examples

To get started with a working project, try the cucumber-java skeleton project which is available from GitHub.

For more examples of how to use Cucumber, have a look at the examples provided in the cucumber-jvm project on GitHub.

If you’d like to try Cucumber with Kotlin, have a look at my blog post.

Note: This tutorial was originally written as part of the new Cucumber documentation. You can find the cucumber documentation project on GitHub. It was adapted a little here to make a stand-alone tutorial.